Black Cattle:

On the Transatlantic Slave Trade and the West India Company

By John Meilink

The West India Company (WIC) was founded on June 3, 1621, during the Eighty Years' War. It was a trading enterprise that had been granted a charter by the Dutch States-General to conduct trade west of the Cape of Good Hope. The Company had the right to maintain a military force, form alliances, and establish colonies.

In the first decades of its existence, the WIC was primarily a military tool of the States-General in the struggle against the Spanish and Portuguese. In a short period, the Company conquered an empire that stretched across large parts of the West African coast, Brazil, and islands in the Caribbean. Privateering also played an important and effective role in the conflict. After the conquest of Dutch Brazil in 1630, the Company increasingly focused on transporting Black slaves from West Africa.

The settlements (factories) of the WIC on the West African coast.

The novel Black Cattle focuses on a single aspect of that history of slavery: the trade on the West African coast. The Dutch at the time had no interest in expansion in Africa. They were after three things: gold, slaves, and ivory (in that order). The West India Company also did not have the military means, and certainly not the manpower, to venture far into the interior.

When the Dutch captured Elmina Castle from the Portuguese in 1637, treaties were quickly made with the local kings. In fact, from the outset, the WIC paid rent to be able to build their forts and conduct trade.

Sources: Het kasteel van Elmina: in het spoor van de Nederlandse slavenhandel in Afrika by Marcel van Engelen, and Brothers in Arms, Partners in Trade: Dutch-Indigenous Alliances in the Atlantic World, 1595-1674 by Mark Meuwese.

The Treaty of Boutry regulated the cooperation between the confederation of the Ahante tribes and the Dutch. Signed on August 27, 1656, the treaty would last for 213 years.

The earliest known agreement of cooperation between the Dutch and Africans was the Treaty of Asebu (1612). Many more would follow.

Monogram of the West India Company

The West India House in Amsterdam, seen from Prins Hendrikkade. Hand-colored reproduction based on a drawing by L.W.R. Wenckebach.

Illustration from Black Cattle. (c) John Meilink

The Europeans mainly fought among themselves: especially the Dutch and the English were constantly at odds. They contested each other’s trading posts, river mouths, watering places, and more, but in their relations with African rulers, they were notably submissive, as they were entirely dependent on the supply of goods from the interior.

A good example of the power dynamics is the story of the king of Fida (in present-day Nigeria), who threatened to expel the Dutch if they did not stop quarreling with the English and the French. They grudgingly complied.

Wikipedia on the WIC.

Black slaves in the hold. Digitally edited image from the movie Bande-annonce de Case Départ (2011)

1687 and 1688 were years in a period when the slave trade was becoming increasingly important, but the supply to the West (Curaçao, Berbice, Suriname) remained a difficult operation for all parties. The West India Company had the exclusive right to trade on the Gold and Slave Coasts, but still had to compete with the English, Brandenburgers, Portuguese, and—especially annoying—smugglers from Zeeland. The French were also lurking.

The West India Company always faced a dilemma: gold (which was mined and supplied by the Africans themselves) was perhaps even more important than slaves, but transporting gold required peace. The slave trade, however, only flourished during times of war between African tribes (as slaves were typically captured enemies). This contradiction naturally led to bargaining and corruption.

In Black Cattle, all parties try to outsmart each other. The batch of illegal slaves was a windfall, but the WIC always had to avoid antagonizing the king of the Denkyira kingdom.

By LM Publishers: Slavery Heritage Guide for the Netherlands

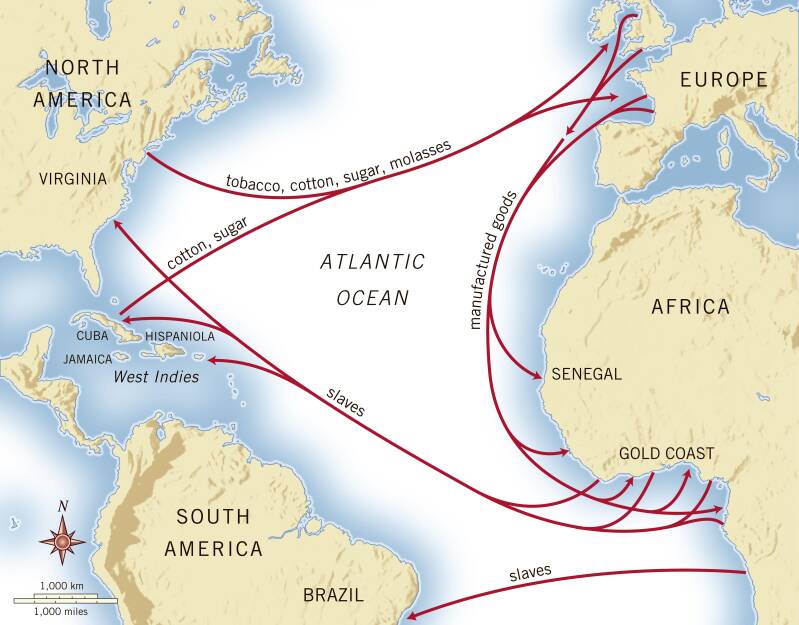

Triangular trade – Transatlantic triangular trade: 1. Ships departed from Western Europe with trade goods, mainly firearms, gunpowder, iron, and textiles. These were exchanged in West Africa with local rulers for slaves, gold, and ivory. 2. From West Africa, ships carrying slaves then sailed to the Caribbean. 3. Return journey to Western Europe with luxury goods such as sugar, rum, coffee, cotton, silver, and tobacco

Source: mejorimagen.eu.

Slaves were bought and sold in a specific unit: the pieza de India. This stood for a healthy, well-built man or woman between 15 and 36 years old. Persons aged 8 to 14 were counted as two-thirds of a pieza, and those 7 years and younger as half a pieza. Infants (children up to two years old) were sold along with their mother. Therefore, the actual number of slaves on a ship did not necessarily correspond to the number of pieza de India registered in the cargo list.

The "peak" of Dutch Atlantic slave trade occurred roughly between 1630 and 1700. With the conquest of part of Brazil from the Portuguese, there was a high demand for cheap labor on the plantations there. The Dutch were quick to take over the trade in Black slaves from the Portuguese; in a short time, they conquered their trading posts on the West African coast. The WIC held a monopoly in this. After the colonization of Suriname and Berbice, the slave trade intensified, but the major boom happened around 1660, when the WIC, through intermediaries (the asientistas, see the book Asiento), almost had exclusive rights to supply slaves to Spanish America. Curaçao became the center of this deplorable trade. However, after 1687, the Dutch were gradually pushed out of the market by the English and the French, mainly due to the opposition of the Spanish Inquisition.

In the 18th century, the combined Dutch/Zeeland market share in the global slave trade to the West had dropped to about 10%, of which more than half was handled by the WIC. Rival England had a share three times as large. The rest of the trade, about 60%, was in the hands of Portugal. The Portuguese operated further south in Africa, mainly from Angola and the large slave depot in Luanda.

The exact number of slaves the WIC actually exported to the West is unknown, as almost all documents from the First WIC (the period before 1674) were lost in a fire in the 19th century. For the period 1674-1740, Henk den Heijer, in his dissertation Goud, ivoor en slaven ("Gold, Ivory, and Slaves"), estimates a total of 190,000 (based on sources from the Dutch Historical Data Archive), of which 43,000 were transported via Elmina. 1680 was still a very productive year for Elmina (it sent out 2,100 slaves), but then the decline set in: during 1687-1689, exports stalled at 2,154, just over 700 per year. When the Komenda Wars broke out shortly after (a fierce dispute between the Dutch and the English), the export collapsed completely.

The highest peak in terms of exports was reached when the Dutchman Balthasar Coymans was an asientista of the Spanish crown: between 1684-1686, almost 16,000 Black Africans were shipped.

Estimated numbers of embarked and disembarked slaves in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. The data comes from http://www.slavevoyages.org/tast/index.faces. The peak was between 1760 and 1850. By then, the WIC no longer played a role; it withdrew from the slave trade in the early 1740s.

Source: TED-Ed - The Atlantic slave trade: What too few textbooks told you - Anthony Hazard.